The Life Story of my teacher Master Wang Qingyu: From Adversity to Mastery

- Sep 21, 2023

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 25, 2025

Born into aristocracy in 1937, Wang Qingyu witnessed China transform through decades of tumultuous change. His journey from privilege to persecution, and ultimately to recognition as one of China's foremost Qigong masters, reveals the mysterious alchemy of the human spirit—how suffering can be transformed into compassion, and adversity into service.

The Making of a Master

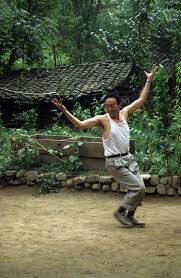

Dr. Wang is now recognized by the Chinese government as an outstanding master of the ancient Daoist healing art of Qigong. His credentials speak to a life dedicated to healing: poolside physician to the Sichuan diving team during the Sixth China Games in 1987, trusted healer to Olympic champions including gold medalist Gao Min, member of China's prestigious Chinese Qigong Academy, and the government's primary consultant for assessing Qigong masters throughout the country.

Having retired from an intensive healing practice in Beijing, Dr. Wang now chairs the Sichuan Society of Daoist Studies in Chengdu, continuing his research and teaching. He is the author of several works including Esoteric Taoist Internal Alchemy Channel and Collateral Qigong and A Glimpse at the Secrets of Daoist Medicine.

As the lineage holder of Daoist Jinjing Internal Alchemy Qigong, one of the most ancient and respected forms of this practice, he represents an unbroken chain of wisdom stretching back millennia.

Qigong, literally meaning "energy work," encompasses both quiet meditation (inner alchemy) and moving meditation designed to open the body's channels and meridians. The practice focuses on four essential components: visualization, specific body postures (mudras), breath, and sound or vibration (mantras). A true Qigong master learns to cultivate essence in the lower abdomen, transmitting this refined energy to others as healing power.

A Privileged Beginning

Wang Qingyu was quite literally born on a military field to a mother who was a general in the army. His early life unfolded within the refined atmosphere of a wealthy landowning family whose men had served as generals since the Qing Dynasty. From childhood, he was immersed in an environment rich with martial arts tradition, classical scholarship, and medical knowledge. His extraordinary memory—able to memorize entire pages of classical texts at a glance—earned him his father's special attention and a privileged education that included piano, private tutoring in the classics, and training with some of China's most renowned martial arts masters.

His father's teaching methods were unforgiving. The young Wang endured being lashed with a whip if he failed to maintain training postures for the required hours. Yet it was this rigorous foundation that would later sustain him through unimaginable hardships.

At age ten, Wang met the figure who would transform his life: Li Jie, a wandering Daoist hermit whose mastery of scholarship, healing, and martial arts had made him a living legend in China's southwestern provinces. Under Li's guidance, Wang became adept in herbalism, fingernail diagnosis, acupressure, and Qigong. More importantly, Li Jie instilled in him the moral stamina and spiritual understanding that would prove essential to his survival.

The Wheel of Fortune Turns

The establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949 shattered Wang's privileged world. Overnight, the landowner class fell from respectability to become "the black kind"—social pariahs whose very existence was considered dirty and shameful. The family's vast wealth, including golden coins requiring twenty-four bearers to transport, was confiscated by the government. Wang found himself with only one set of underwear and insufficient food.

Personal tragedy compounded political upheaval. His mother had died when he was two; his father died when he was thirteen. Though surrounded by his father's other wives and children, Wang was essentially an orphan—even facing several poisoning attempts by his own family members. At thirteen, already mature beyond his years through his rigorous education, Wang faced a world that had turned completely upside down.

Education in Adversity

Assigned to teach middle school in the harsh Tibetan regions of western Sichuan Province—China's equivalent of Siberia—Wang found himself in dangerous and desolate conditions. Yet he continued his studies, apprenticing with local herb collectors and deepening his understanding of therapeutic plants. During this period, his calling to become a Daoist healer crystallized, and he dedicated his life to helping the sick.

The Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s brought new dangers. Practicing traditional healing was branded "feudal superstition," punishable by imprisonment or worse. Wang continued treating patients in secret, always at risk of denunciation by the very people he helped. The political climate fostered a system of betrayal where people protected themselves by reporting others.

One morning, Wang arrived at school to find "wall newspapers" posted with his name and accusations: claims that he cheated patients for food, practiced without a license, and communed with ghosts during his secret 3 AM Qigong sessions. The accusations culminated in the declaration: "Your grandfather exploited the people, your father exploited the people, and now you are doing the same thing; from no-goods there can only be no-goods."

Wang was imprisoned in what was called the "ox-stall," forced to write endless confessions about his supposed crimes. Guards would tear up his reports and demand more, torturing him and depriving him of sleep. His pregnant wife faced pressure to divorce him. Yet he emerged unbroken, guided by the Daoist principle of the turtle that keeps its head safely within its shell.

Moments of Illumination

Despite the external chaos, Wang experienced profound moments of spiritual awakening that sustained him through the darkest times. One pivotal experience came as his middle school class sang a traditional song about the Sword Gate Pass in northern Sichuan—a narrow mountain opening where, historically, ten defenders could hold off entire armies pursuing fleeing emperors.

As they reached the final line—"This is the place where we can unite with the wonders of nature"—Wang experienced a profound realization. He understood his individual pain as merely a speck of dust in comparison to the vastness of nature. If one could reunite with this source, personal suffering became bearable, even meaningful. This insight filled him with love for all people, rivers, streams, and mountains, transforming his perspective permanently.

Another crucial moment came when Wang discovered his healing abilities firsthand. While practicing Qigong in the remote countryside, he injured his ankle and found himself alone and unable to walk. Applying the healing techniques he had learned but never fully trusted, he experienced immediate relief. This direct experience of healing power crystallized his life's purpose.

From that point forward, Wang secretly treated injuries and illnesses, combining herbs with Qigong and acupressure with remarkable success. Despite the dangers, people throughout the region came to know him as a special healer. In a strange paradox of the times, patients who loved him for his help had to publicly pretend hatred because of his "black kind" status. Yet their gratitude manifested in small gifts—ears of corn or wild mushrooms thrown through his window at night.

The Renaissance

In 1976, China's political winds shifted again. New leaders, many of whom had themselves been persecuted as "black kinds," declared an end to the class-based discrimination. When the government launched national competitions to identify great healers, Wang was willing to participate despite years of suppression.

The transformation was dramatic. From an obscure country doctor treating a few patients in secret, Wang became one of only three healers selected from the entire nation. His patient load expanded from dozens to hundreds, including high-ranking officials suffering from strokes and paralysis. His success rate was extraordinary—paralyzed patients walked again under his care.

This period marked Wang's full emergence into mastership, operating at the highest level of his potential. Yet success brought its own challenges and temptations.

The True Nature of Mastery

When asked about mastery, Wang explains that the Chinese term "dashi" contains two concepts: "da" (big) and "shi" (teacher)—literally, a teacher of teachers who stands out from the masses. But true mastery encompasses both greatness of mind and greatness of heart. It implies that one's accomplishments should benefit others, not merely oneself. Masters maintain what Wang calls "aloofness"—not arrogance, but a noble quality that elevates them above the ordinary material world.

This traditional understanding, rooted in Daoism and Buddhism, still carries religious implications even as the term has spread to secular contexts. A master uses knowledge for the common good, maintaining ethical standards that transcend personal gain.

Wang identifies several elements essential to mastery: innate talent (pre-natal factors), environment and teachers (post-natal factors), and most importantly, human spirit—an instinct-like drive to refine knowledge and talents regardless of circumstances. Paradoxically, external difficulties often strengthen this drive, as they did in his own life.

The Beloved Teacher

Central to Wang's development was his relationship with Li Jie, the wandering Daoist hermit who became his primary teacher. Li Jie embodied three qualities that made him a true master: profound "aloofness" or perspective that saw beyond petty human concerns; deep love for all living things and nature; and extraordinary technical knowledge of both internal and external arts.

Known as the "Hermit of the Ubiquitous Smile," Li Jie possessed the rare ability to heal broken bones in minutes or break tree branches from a distance—powers that Wang witnessed personally, distinguishing his teacher from the many false masters he would later encounter in his official capacity. But beyond technical skill, Li Jie radiated an internal power, a deep source within himself that transformed all who met him.

It was Li Jie who gave Wang his name "Qingyu," from the Book of Changes, meaning that good deeds for others are never wasted but return with ever greater abundance. This name became a source of strength during the darkest times.

Living the Teaching

Wang's greatest regret is that he never had the opportunity to "repay" his teacher before Li Jie's death—never able to show him how completely he had absorbed and lived according to his teacher's spirit. Yet the teacher's presence remains vivid and sustaining.

When Wang speaks of Li Jie, tears come naturally. He describes a Renaissance figure: martial artist, healer, calligrapher, painter who created art with his long fingernails, face and palm reader, eternal student. But most remarkable was Li Jie's inner quality—not a smile on his face, but deep laughter within his heart. Patients would leave his presence thinking, "What's my pain? My disease really doesn't matter."

There was, Wang explains, an upwelling of light from Li Jie's chest that made people realize their troubles were insignificant. Healing began simply from being in his presence. This same source continues to feed Wang regardless of life's difficulties, accessed simply by thinking of his beloved teacher.

The Continuing Journey

Even after achieving recognition as one of China's foremost healers, Wang maintains that the journey never ends as long as breath remains. At sixty, for the first time in his life, he had the freedom to practice Qigong intensively, conduct research, work with herbs, and live the ideal scholar's life he had long envisioned. Now he is 93, retired, living in the mountains and maintaining his profound presence through the practice of his students.

Fame and wealth hold no attraction for him. From the Daoist perspective, being better doesn't mean elevating oneself above others, but bringing out one's own best potential. When acclaim came after healing Olympic divers, Wang was grateful mainly that he had not wasted his teacher's gifts—that he had made good use of what he had been taught.

True to Daoist wisdom, Wang knows that what rises must fall. The years of hardship trained him to "duck" when success threatens to bring unwanted attention. He took no money or special privileges from the famous people he healed, wanting only to prove to himself that he possessed the power to help them.

The Eternal Teaching

Wang's story illuminates the mysterious process by which suffering can be transformed into service, adversity into wisdom, and individual pain into universal compassion. His life demonstrates that true mastery lies not in personal achievement but in the cultivation of qualities that benefit all beings—the greatness of heart that must accompany greatness of mind.

In a world often focused on external success, Wang Qingyu's journey reminds us that the most profound teachings often emerge from the deepest difficulties, and that the greatest masters are those who transform their own healing into a gift for others. His teacher Li Jie's presence continues through Wang's work, and Wang's influence will undoubtedly continue through the countless lives he has touched and the students he continues to guide.

The stream of light that flowed from his teacher's heart now flows through Wang to others, carrying forward an ancient wisdom that recognizes no boundaries of time, politics, or circumstance—only the eternal human capacity to transform suffering into healing, and individual awakening into service to all life.

A truly remarkable and inspiring story! I hope you will consider writing his biography one day!